For all the hype, anyone who has used any of the current crop of so called “intelligent” programs knows they don’t actually comprehend a single word you say to them. The problem has been that intelligence requires knowledge to work but knowledge is also the product of intelligence.

There is no such thing as Artificial Intelligence. That is, as of today, it does not exist except as a idea or more properly as many ideas since people, even experts, are not in agreement about what it might be. Whatever it is, we have been expecting it for some time, almost since the dawn of computing.

Alan Turing, in his 1950 paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” proposed the following question: “Can machines do what we (as thinking entities) can do ?” To answer it, he described his now famous test in which a human judge engages in a natural language conversation via a text interface with one human and one machine, each of which try to appear human; if the judge cannot reliably tell which is which, then the machine is said to pass the test.

The Turing Test bounds the domain of intelligence without defining what it is. We can only recognize intelligence by its results. However, over the more than 50 years since Turing’s formulation, the term has been loosely applied and is now often used to refer to software that does not by anyone’s definition enable machines to “do what we (as thinking entities) can do,” but rather merely emulate some perceived component of intelligence such as inference or some structure of the brain such as a neural network. Recently the term “Artificial General Intelligence” (AGI) has come into use to refer precisely to the domain as Turing defined it.

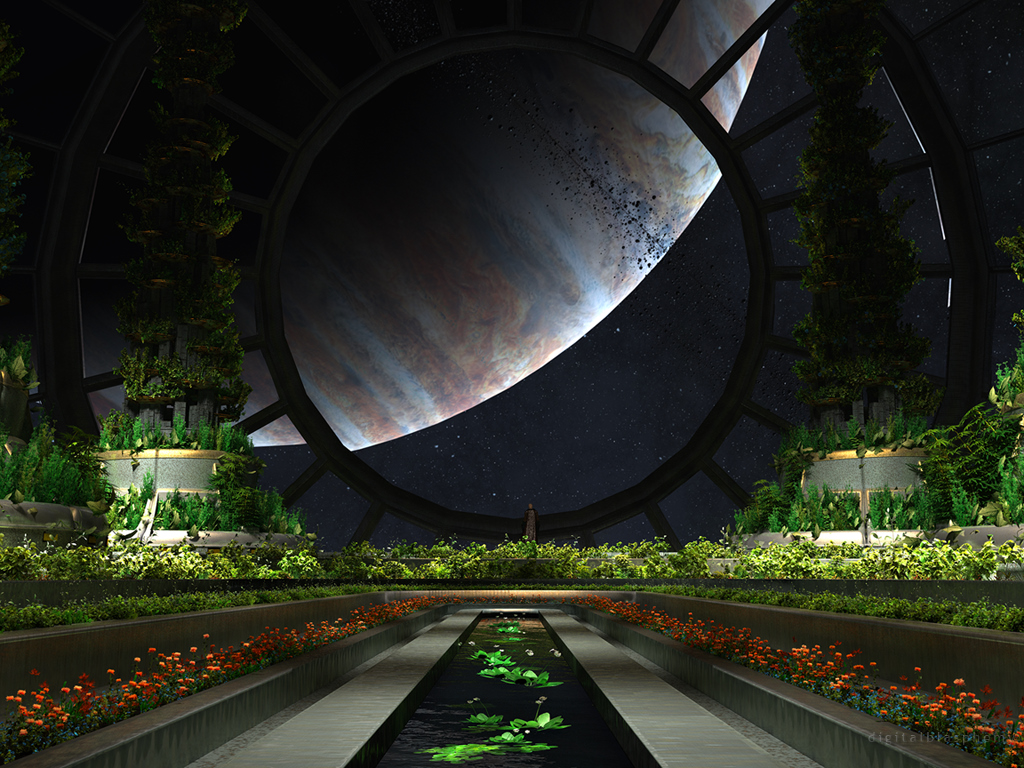

We were given a tantalizing (if scary) vision of a super-intelligent AI named HAL the 1968 book and movie “2001: A space Odyssey” written by Science Fiction visionary Arthur C. Clarke. HAL was, according to the story, turned on in 1991. Sir Arthur missed the mark by a long way. More than forty years after the story was written, all we have is a Jeopardy playing super computer and applications like Apple’s Siri (Speech Interpretation and Recognition Interface) which uses algorithms to convert natural language input text into search engine queries. These technologies have nothing resembling actual comprehension of the world.

Why has “real” AI or AGI been so long in coming? The fundamental difficulty has been, as Turing pointed out, that we can only know we are the right track in developing AI software when it does useful things. Intelligence, however, requires knowledge before it can do anything useful. (Consider the practical difference between Einstein and a Cro-Magnon man with a similar IQ.) So we have a chicken-and-egg dilemma because knowledge is the product of intelligence.

One approach to this problem has been to develop “knowledge-based systems.” These systems have attempted to encode human knowledge (usually in the form of rules and logical assertions) directly in a so-called knowledge-base and then apply intelligent algorithms to that to do useful things. This approach does work and a few so-called “expert systems” were produced that did in fact do useful things in limited domains. But the approach has turned out to be limited by the practical challenges of building large knowledge-bases.

An attempt to build such a system that would be large enough to exhibit common-sense knowledge of the world has been underway for more than twenty years at Cyc Corporation. The Cyc knowledgebase consists of a very large number of simple elements (@300,000) which are processed by 3 million logical assertions. By the team’s own estimates it currently represents only 2% of human common sense.

What is needed then is not a comprehensive knowledge base but a compact specification for generating knowledge much as DNA is a compact specification for generating an organism. One of the most amazing things about human development is the way children bootstrap their way into learning language and with it, common-sense knowledge of the world. Clearly humans have such an innate compact specification for generating a knowledge since they achieve common-sense with a very limited vocabulary. A vocabulary of a few hundred words along with the cognitions they represent are sufficient to learn an arbitrary large number of new concepts.